How to Build APIs That Don't Suck

After wrestling with nightmare APIs—think GETs that create, POSTs that hide data, and surprise HTML errors—I vowed to build integrations that don’t suck. Here’s my hard-won blueprint for APIs that developers actually love.

The API Integration Nightmare That Changed Everything

We love to boast as backend developers about scaling services and handling millions of requests. But let's get real—most of the time, we're just developers managing a spaghetti mess of API integration chaos.

I learned this the hard way when I was tasked with integrating APIs for multiple logistics providers. What should have been a straightforward project turned into months of daily fire-fighting. Provider A would create resources with GET calls (yes, really). Provider B would return resource data only on POST requests. Provider C would randomly send HTML error pages that would completely break our JSON parsing. And don't get me started on the ones who'd change their schema without any announcement, leaving our production system choking on unexpected field types.

Instead of building something meaningful, I was spending my days debugging why FedEx suddenly started returning addresses in a completely different format, or why DHL's API decided that "success" responses should sometimes have a 500 status code. It was torturous. I swore I'd never put another developer through that hell.

That experience stuck with me through every API I've built since. When I started working on Vade AI, I realized we're fundamentally in the business of solving API integration pain—connecting AI-native no-code platforms with tools like Slack, WhatsApp, Telegram, Discord, and dozens of other services. The people who solve this kind of pain become billionaires. Maybe I could be among them.

That's why I'm writing this blueprint. After a decade of being burned by terrible APIs and slowly learning what actually works, these are the battle-tested principles that have kept me sane and our integration partners happy.

Rule #0: Don't Get Pedantic About "REST"

Look, we all know that one developer who'll interrupt your design review to lecture about how your API "isn't really RESTful" because you're missing HATEOAS links or whatever. Don't be that person.

Most developers today understand "REST" as HTTP-based APIs with noun-based URLs. That's good enough. Focus on building useful, predictable APIs that don't make people want to quit programming altogether.

Rule #1: Use Plural Nouns (And Other Obvious Things That Aren't So Obvious)

This one should be a no-brainer, but I've seen enough APIs that use singular nouns to know it's worth repeating:

;; GOOD - From our apps endpoint

["/v1/apps"

{:get {:handler handlers/get-apps}

:post {:handler handlers/create-app}}]

["/v1/apps/{id}"

{:get {:handler handlers/get-app-by-id}

:put {:handler handlers/update-app}

:delete {:handler handlers/delete-app}}]

;; BAD - Don't do this

["/v1/app/{id}" ...] ; Inconsistent and weird

It's an arbitrary convention, but it's well-established. Breaking it is like using spaces instead of tabs in a Python codebase—technically it works, but you're going to annoy everyone.

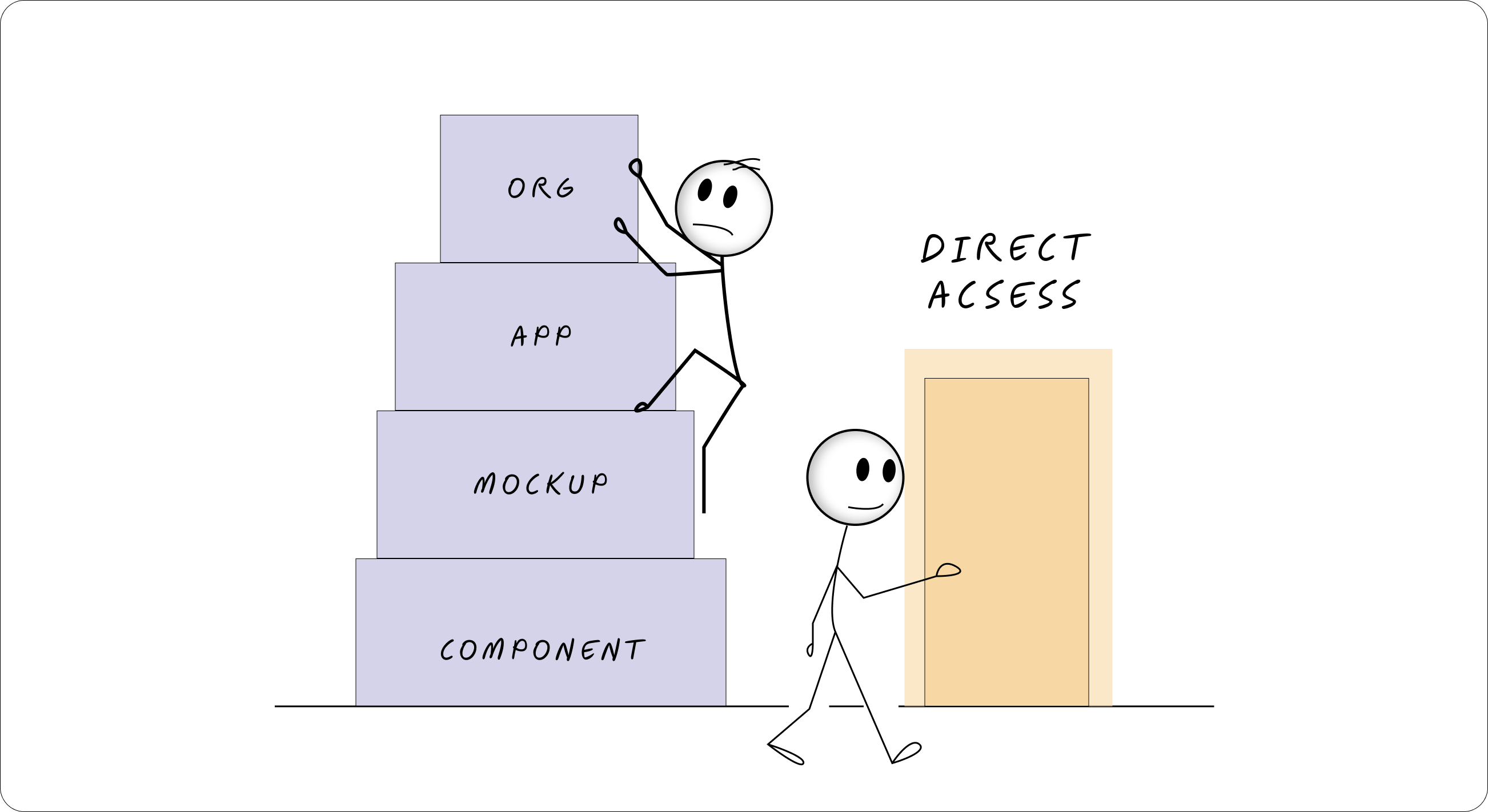

Rule #2: Don't Build Your Database Schema Into Your URLs

I see this mistake everywhere. Developers get excited about showing off their relational model and end up with URLs that look like Russian nesting dolls:

;; BAD - Overly nested just because the data is related

"/v1/orgs/{org-id}/apps/{app-id}/mockups/{mockup-id}/components/{component-id}"

;; GOOD - Keep it simple since mockup-id is globally unique

"/v1/mockups/{mockup-id}"

Here's what we do in our API: if an ID is globally unique (which it should be), you don't need to nest it. Our app-id in the mockups endpoint is there for convenience and scoping, not because it's technically required:

;; This is fine for creating mockups under an app

["/v1/apps/{app-id}/mockups"

{:post {:handler handlers/create-app-mockup}}]

;; But for operations on specific mockups, we keep it flat

["/v1/mockups/{mockup-id}"

{:get {:handler handlers/get-mockup}

:put {:handler handlers/update-mockup}}]

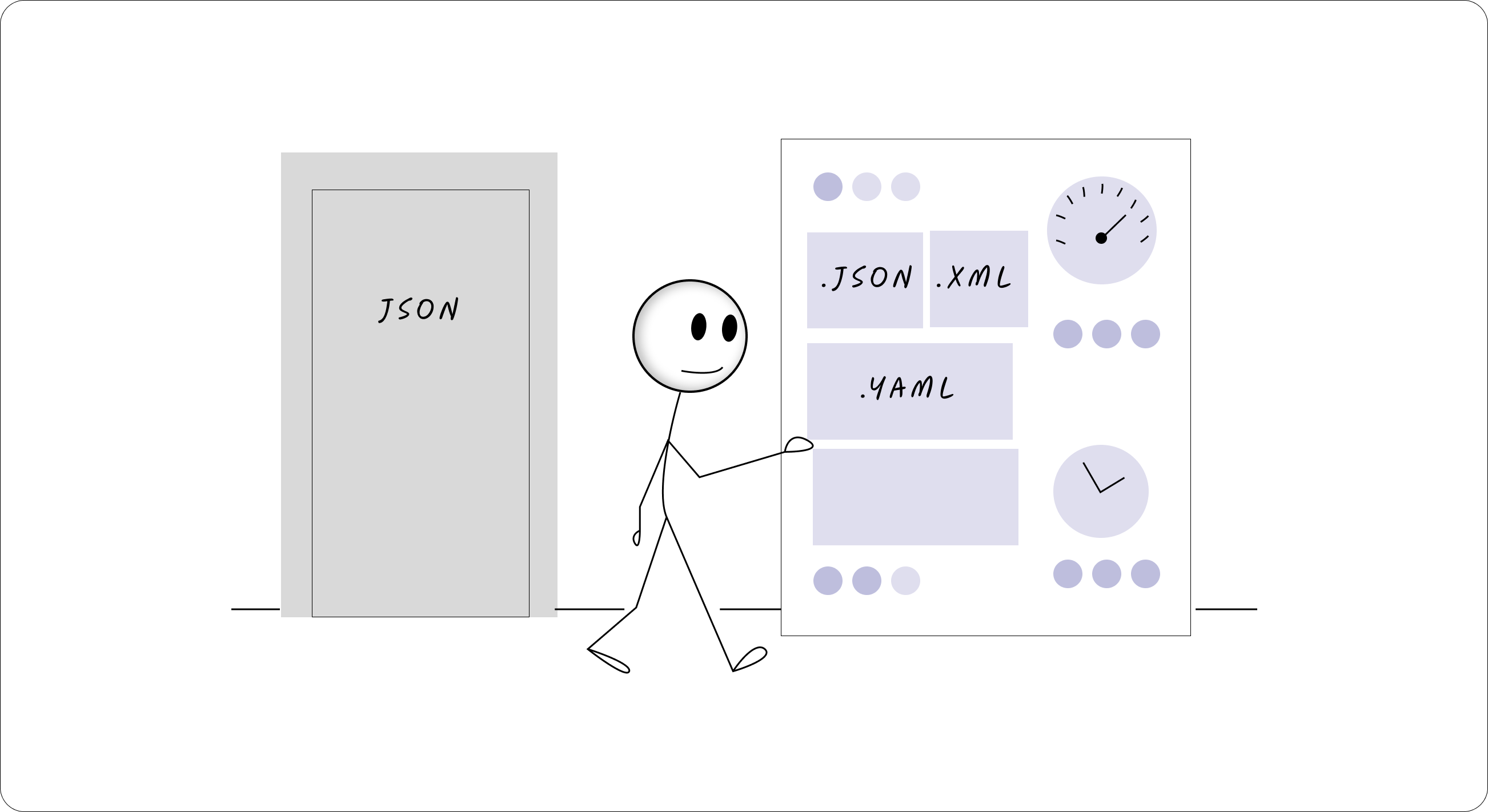

Rule #3: JSON is King (But Be Smart About It)

Don't add .json extensions to your URLs. It's 2025, not 2005. JSON should be your default response format, and if clients need something else, they can use proper HTTP headers.

;; GOOD

(defn success-response

[data & {:keys [status] :or {status 200}}]

{:status status

:headers {"Content-Type" "application/json"}

:body {:success true

:data (v.ds/deep-name-keyword data)}})

;; BAD - Don't put this in your URLs

"/v1/apps.json" ; Nope

"/v1/apps.xml" ; Double nope

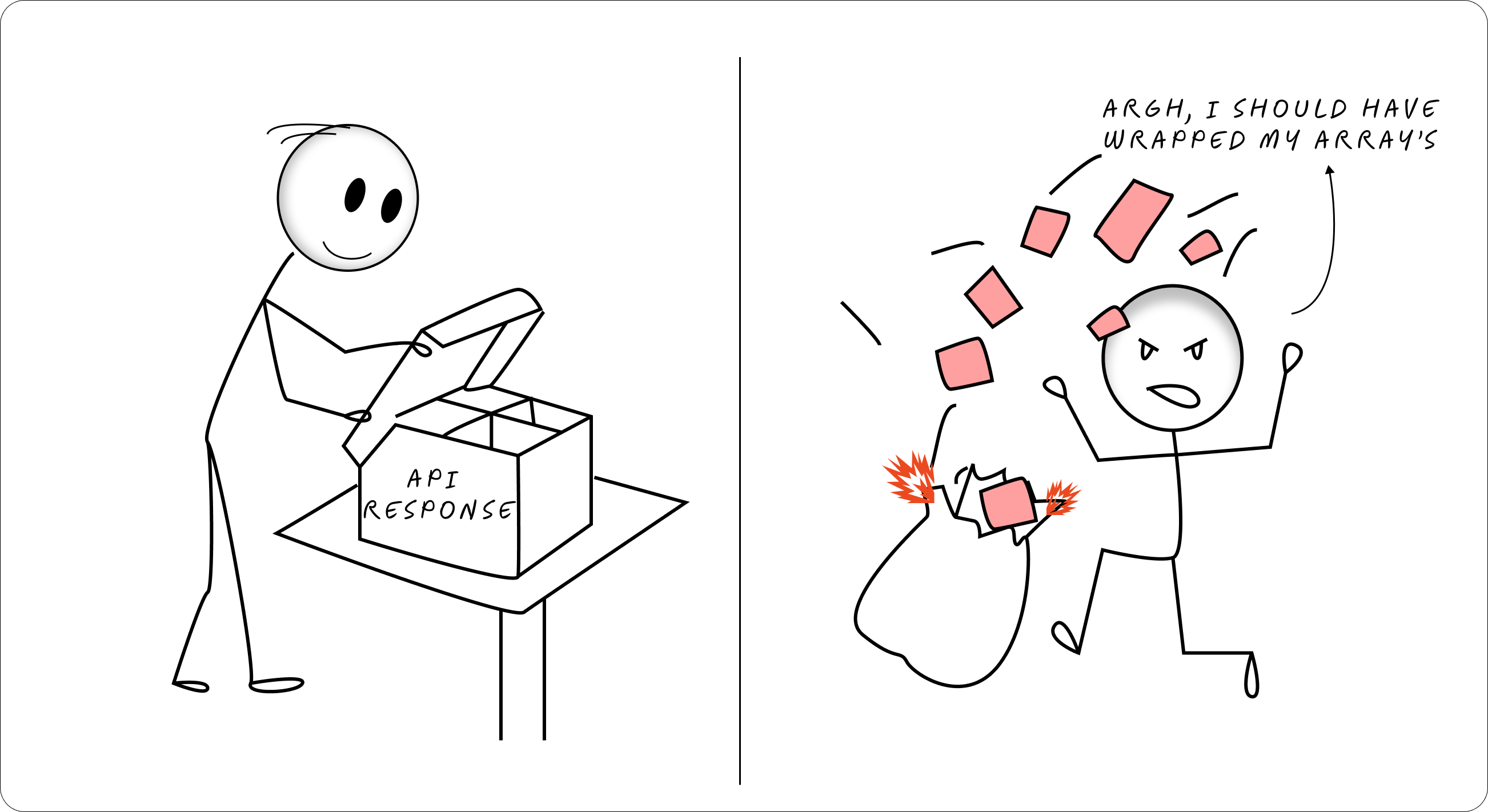

Rule #4: Wrap Your Arrays (Future You Will Thank You)

Never return naked arrays from your API endpoints. Always wrap them in objects. This is one of those rules that seems pointless until you need to add pagination or metadata and suddenly realize you've painted yourself into a corner.

;; GOOD - Our list response pattern

(defn list-response

[items & {:keys [has-more next-token total-count]}]

{:status 200

:body {:success true

:data (v.ds/deep-name-keyword items)

:total-count (or total-count 0)

:has-more has-more

:next-token next-token}})

;; Returns:

{

"success": true,

"data": [

{"id": "app_123", "displayName": "My App"},

{"id": "app_456", "displayName": "Another App"}

],

"totalCount": 42,

"hasMore": true,

"nextToken": "page_2"

}

;; BAD - Naked array

[

{"id": "app_123", "displayName": "My App"},

{"id": "app_456", "displayName": "Another App"}

]

When you need to add pagination later (and you will), you can do it without breaking existing clients. Trust me on this one.

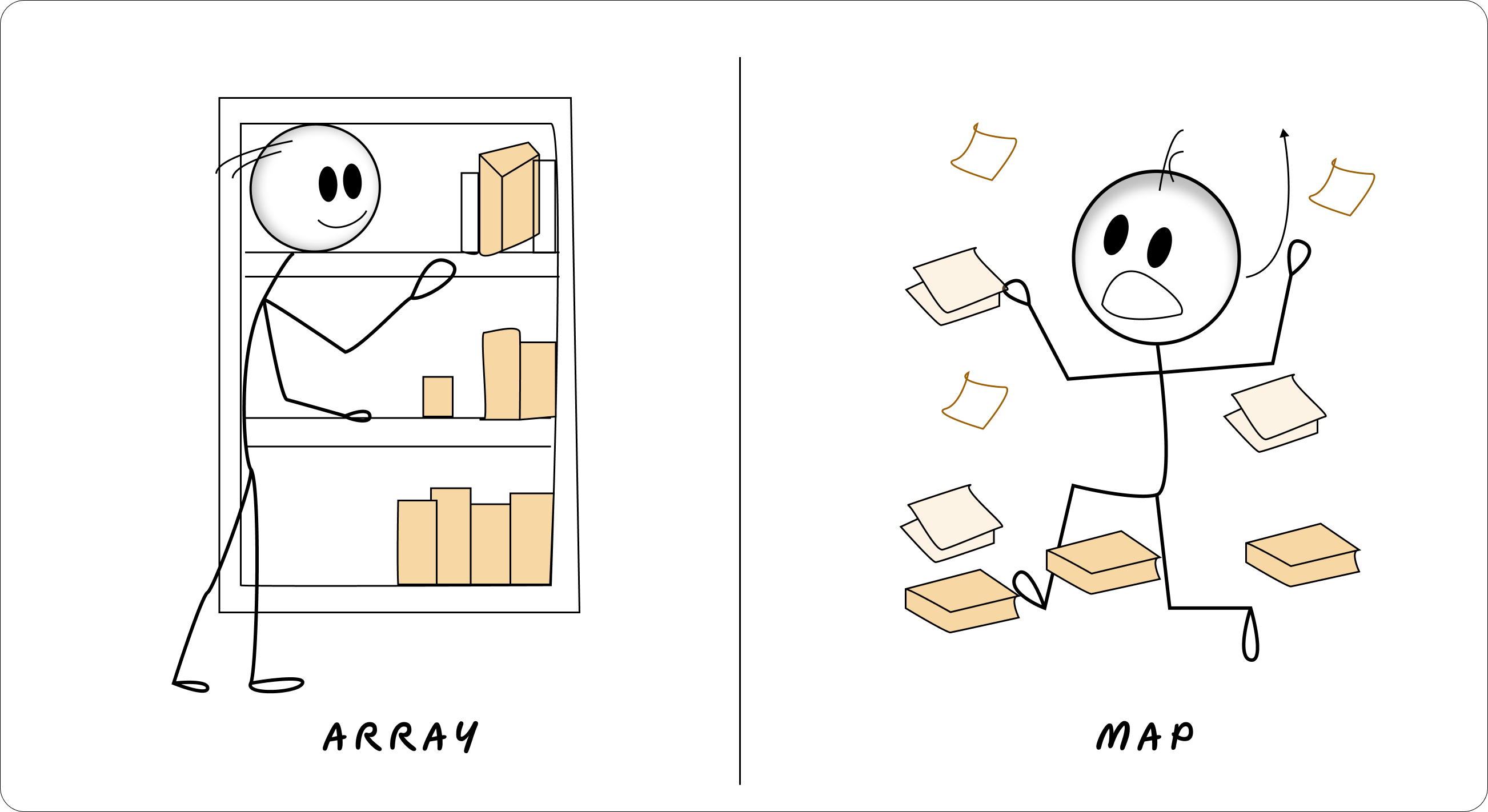

Rule #5: Avoid Map Structures in Responses

Maps might seem convenient, but they're a maintenance nightmare. Use arrays of objects instead:

;; BAD - Map structure

{

"app_123": {"id": "app_123", "name": "My App"},

"app_456": {"id": "app_456", "name": "Another App"}

}

;; GOOD - Array structure

{

"success": true,

"data": [

{"id": "app_123", "name": "My App"},

{"id": "app_456", "name": "Another App"}

]

}

Why? Because your "natural" keys might change, and arrays are easier to work with in most programming languages. Converting an array to a map is a one-liner if your client needs random access.

Rule #6: String IDs Are Your Friends

Always use strings for identifiers, even if your database uses integers:

;; GOOD - String IDs with prefixes

(def app-schema

[:map

[:id :string] ; Actually "app_12345" in responses

[:org-id {:optional true} [:maybe :string]]

...])

;; Our ID generation

(defn create-app

[{:keys [parameters ctx]}]

(let [app-data {:id (str "app_" (u.id/random)) ; Prefixed string ID

:display-name (:display-name (:body parameters))

...}]

...))

String IDs are incredibly flexible. They can encode version information, support composite keys, and won't break when you need to merge databases or migrate platforms. Plus, no type confusion in client code—everything is just a string.

Rule #7: Prefix Your IDs (Make Debugging Less Painful)

Take a page from Stripe's playbook and make your IDs self-describing:

;; Our ID prefixes

"app_1234567890" ; Application ID

"org_9876543210" ; Organization ID

"usr_1122334455" ; User ID

"tpl_5566778899" ; Template ID

"cmp_4433221100" ; Component ID

When someone pastes an ID into Slack at 11 PM asking "What is this?", you'll immediately know what type of resource it represents. Your support team will send you flowers.

Rule #8: Don't Use 404 for "Resource Not Found"

This is controversial, but hear me out. HTTP 404 can come from many layers of your stack—load balancers, proxies, routing issues, etc. When you return 404 for "resource not found," your client can't distinguish between "the resource doesn't exist" and "something is misconfigured."

;; Our approach - Use 410 GONE for missing resources

(defn get-app-by-id

[{:keys [parameters ctx]}]

(let [app-id (get-in parameters [:path :id])

app (model/find-by-id ctx app-id)]

(if app

(responses/success-response app)

(responses/error-response "resource_not_found"

"App not found"

:status 410)))) ; 410 instead of 404

This is especially important for DELETE operations. If your delete endpoint returns 404 and a network issue also returns 404, your retry logic might think the delete succeeded when it didn't.

Rule #9: Consistency is Everything

Looking at you, APIs with 17 different schemas for the same concept. Here's how we keep things sane at Vade AI:

;; Consistent response format across all endpoints

(defn success-response [data & opts] ...)

(defn list-response [items & opts] ...)

(defn error-response [type message & opts] ...)

;; Consistent field naming (kebab-case internally, camelCase in JSON)

(def app-schema

[:map

[:display-name :string] ; Becomes "displayName" in JSON

[:created-at :instant] ; Becomes "createdAt" in JSON

[:org-id :string]]) ; Becomes "orgId" in JSON

Pick your conventions early and stick to them religiously. Use tooling to enforce consistency—our v.ds/deep-name-keyword function automatically converts between kebab-case and camelCase.

Rule #10: Structure Your Errors (Your Future Self Will Thank You)

Random error messages are the enemy of good integration experiences. Structure your errors consistently:

(def error-registry

{::app-not-found

{:type "resource_not_found"

:message "Application not found"

:status 410

:code "APP_NOT_FOUND"

:description "The requested application does not exist or has been deleted"}

::invalid-app-name

{:type "validation_error"

:message "Invalid application name"

:status 400

:code "INVALID_APP_NAME"

:description "Application name must be between 1 and 100 characters"}})

(defn throw-app-not-found [app-id]

(throw (ex-info "App not found"

{:type ::app-not-found

:app-id app-id})))

This gives you a central place to manage all your error scenarios and makes client error handling much more predictable.

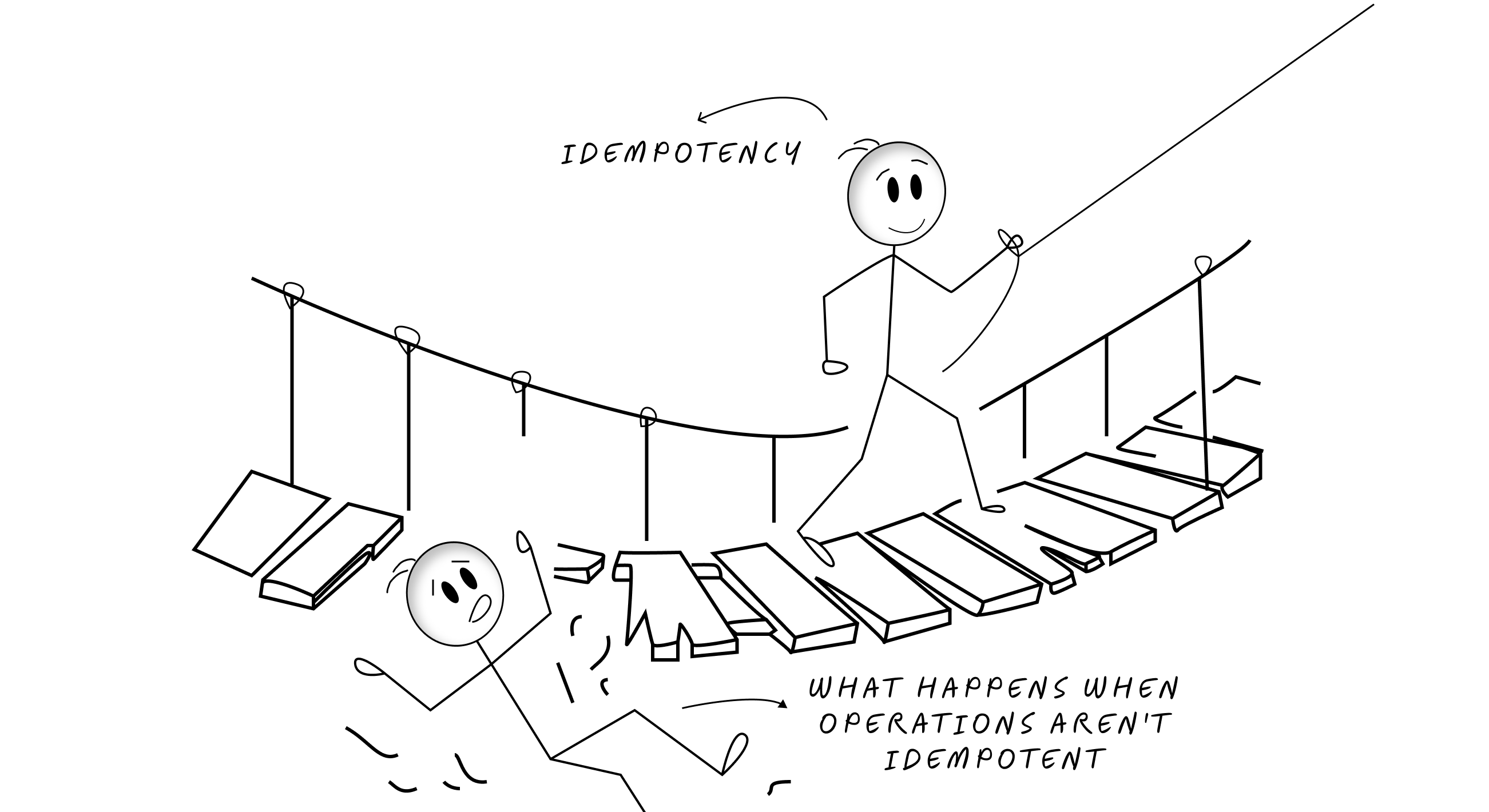

Rule #11: Idempotency is Not Optional

If your API creates or modifies resources, you need idempotency mechanisms. Period. The network is unreliable, and your clients need to be able to retry operations safely.

;; Option 1: Client-provided idempotency keys

(def app-create-body-schema

[:map

[:display-name :string]

[:description {:optional true} :string]

[:idempotency-key {:optional true} :string]]) ; Add this

;; Option 2: Let clients pick IDs (our preferred approach)

(def app-create-body-schema

[:map

[:id :string] ; Client provides the ID

[:display-name :string]

[:description {:optional true} :string]])

(defn create-app

[{:keys [parameters ctx]}]

(let [{:keys [id display-name]} (:body parameters)]

(try

(model/create! ctx {:id id :display-name display-name ...})

(catch ExceptionInfo e

(if (= (:type (ex-data e)) ::duplicate-id)

(responses/error-response "duplicate_resource"

"App with this ID already exists"

:status 409

:existing-id id)

(throw e))))))

When dealing with conflicts, return 409 CONFLICT and include the existing resource ID in the response so clients can continue their workflow.

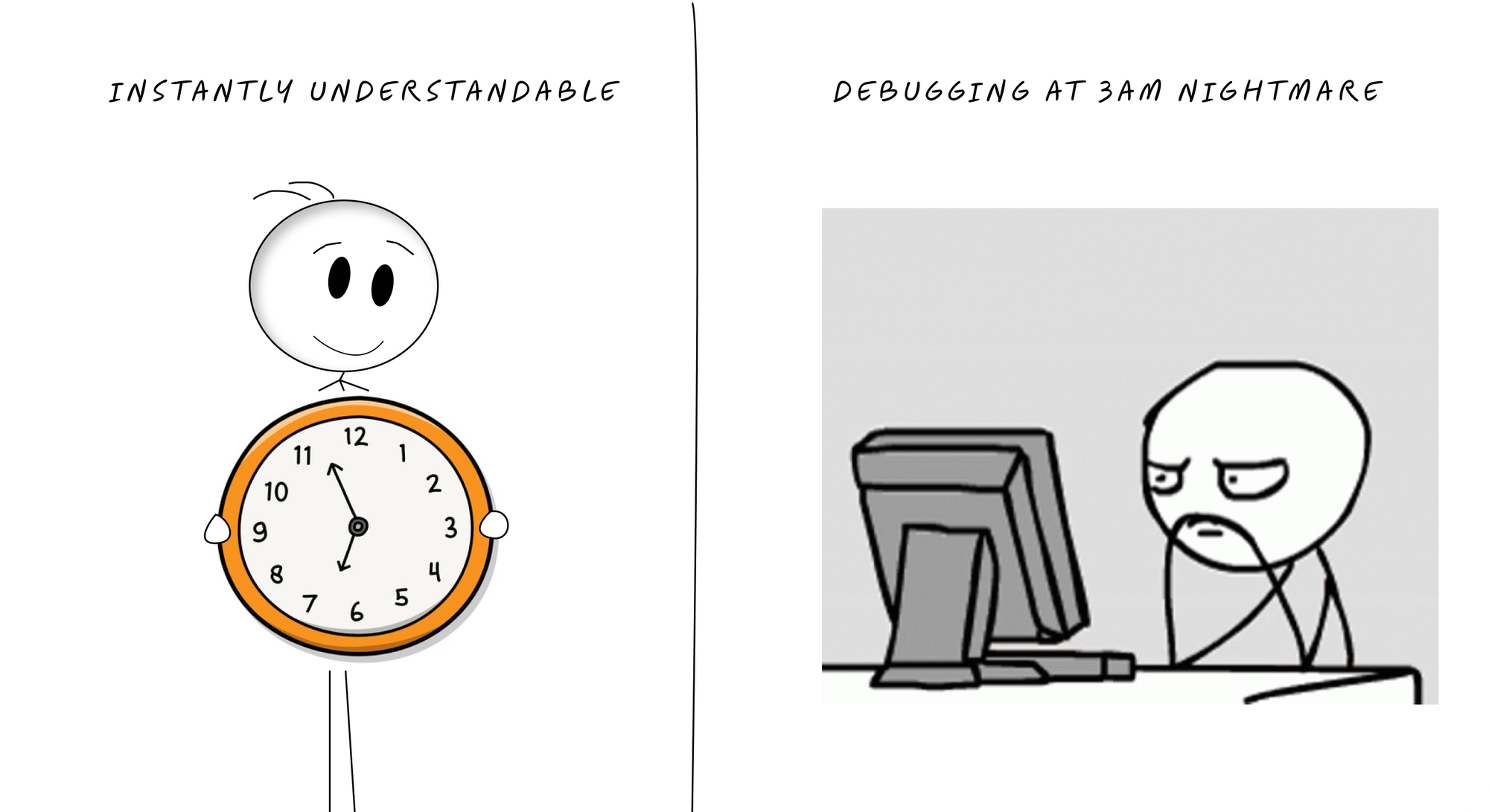

Rule #12: Timestamps Should Be Human-Readable

Use ISO8601 strings for all date/time values. Yes, strings. Not milliseconds since epoch, not custom date formats—ISO8601 strings in UTC:

;; GOOD

{

"id": "app_123",

"displayName": "My App",

"createdAt": "2025-01-20T15:30:45.123Z",

"updatedAt": "2025-01-20T15:30:45.123Z"

}

;; BAD

{

"createdAt": 1705754445123, ; Good luck debugging this at 3 AM

"updatedAt": "1/20/2025" ; What timezone? What time?

}

Human readability matters more than you think. When you're debugging a production issue and trying to correlate timestamps across different systems, you'll appreciate being able to read the date without a calculator.

The Vade AI Approach: Our API Architecture

Here's how we've structured our API at Vade AI to follow these principles:

File Organization

bases/api/src/com/vadelabs/api/

├── apps/

│ ├── routes.clj ; HTTP route definitions

│ ├── handlers.clj ; Request handling logic

│ ├── spec.clj ; Malli schemas

│ └── model.clj ; Database operations

├── utils/

│ └── responses.clj ; Standardized response helpers

├── errors.clj ; Centralized error definitions

└── schemas.clj ; Common schemas

Route Definition Pattern

;; Clean, documented routes with consistent structure

(def routes

["/v1/apps"

{:tags ["Apps"]

:auth {:required? true}}

[""

{:get {:summary "List all apps"

:parameters {:query spec/apps-query-params-schema}

:responses {200 {:body spec/list-response-schema}

401 {:body schemas/error-response-schema}}

:handler handlers/get-apps}}]

["/{id}"

{:get {:summary "Get app by ID"

:parameters {:path spec/app-path-params-schema}

:responses {200 {:body spec/single-response-schema}

410 {:body schemas/error-response-schema}}

:handler handlers/get-app-by-id}}]])

Handler Pattern

;; Consistent handler structure

(defn get-apps

[{:keys [parameters ctx]}]

(let [{:keys [page limit]} (:query parameters)

apps (model/find-all ctx)]

(responses/list-response apps)))

(defn create-app

[{:keys [parameters ctx]}]

(let [app-data (assoc (:body parameters)

:org-id (get-in ctx [:org :id])

:owner-id (get-in ctx [:profile :id]))

created-app (model/create! ctx app-data)]

(responses/success-response created-app :status 201)))

Testing Your API Design

Here's a simple checklist we use to validate our API endpoints:

- Can you understand what each endpoint does from the URL alone?

- Are error messages actionable?

- Can you add new fields without breaking existing clients?

- Is the authentication/authorization pattern consistent?

- Do all endpoints return the same response structure?

- Can operations be safely retried?

Common Pitfalls We've Learned to Avoid

The "Version Creep" Problem

Don't version every little change. Add new optional fields instead of creating /v2 for minor modifications.

The "God Parameter" Anti-pattern

Avoid endpoints that do completely different things based on query parameters:

;; BAD - One endpoint, many behaviors

GET /v1/apps?action=list

GET /v1/apps?action=search&q=term

GET /v1/apps?action=export

;; GOOD - Separate endpoints for different actions

GET /v1/apps

GET /v1/apps/search?q=term

POST /v1/apps/export

The "Everything Is a POST" Disease

Use HTTP methods correctly. If it's idempotent, use PUT. If it's safe, use GET. Don't make everything a POST because it's "easier."

The Bottom Line

Good API design isn't about following every rule in the REST handbook—it's about empathy. Every time you make a design decision, ask yourself: "If I were integrating with this API at 5 PM on a Friday, would this make me happy or make me want to switch careers?"

Your future self, your teammates, and every developer who has to integrate with your API will thank you for following these principles. And trust me, 3 AM debugging sessions become a lot less painful when your API responses actually make sense.

Remember: A great API is like a good joke—if you have to explain it, it's probably not that good.

Quick Reference: The Vade AI API Checklist

- [ ] URLs use plural nouns

- [ ] IDs are prefixed strings

- [ ] Responses are wrapped in objects

- [ ] Errors are structured and actionable

- [ ] Timestamps are ISO8601 strings

- [ ] Operations are idempotent

- [ ] Field naming is consistent

- [ ] Documentation is embedded in routes

- [ ] Authentication is standardized

- [ ] Pagination is built-in from day one

Now go forth and build APIs that don't suck. Your users (and your future self) will love you for it.

Want to see these principles in action? Check out our API documentation or dive into our open-source components to see how we implement these patterns in practice.